When will humans be able to cure AIDS?

Scientists are on the road to a cure for AIDS The fight against AIDS is similar to the fight against many types of cancer. In the 1950s, childhood leukemia was nearly fatal. Eventually, drugs were developed that could provide months or years of relief from this cancer, but it always came back. In the 1970s, researchers discovered that leukemia cells lurked in the central nervous system, and it was only then that targeted treatments were developed to get rid of them. Today, the cure rate for childhood leukemia is 90%. In the same year that the invention of the Daiichi Ho cocktail therapy was introduced in 1996, predicting that 27 months of antiretroviral treatment would cure AIDS, Robert Siliciano announced to the world the unfortunate catastrophe of the existence of a latent, persistent reservoir of HIV. Since then, scientists around the world have been battling the virus for nearly two decades with one goal in mind - to clear the reservoir and cure AIDS once and for all. In July 2014, at the 20th World AIDS Conference in Melbourne, Australia, Sharon Lewin, an infectious disease specialist from Monash University, said, "At the moment, we're probably still looking to do what we can to achieve long-term remission." As of today, most experts agree that a functional cure for AIDS, i.e., long-term remission that frees patients from lifelong treatment, is achievable, and even the most cautious AIDS researchers believe that a cure for AIDS will eventually be realized after long-term remission treatment. For only years of tracking patients who are off all drugs will make it clear whether a true cure for AIDS has been found, and the optimal therapy will not be determined until the body is clearly and accurately tested for how much latent virus it contains. PREFACE: From the discovery of the first case of AIDS in 1981 to the surprising cocktail of therapies in the 1990s. A deadly virus was tamed into a chronic condition. The next step was to find a cure. Scientists are naturally curious, and AIDS researchers have learned humility over the years. Scientific developments have always centered around uncertainties, intertwined with frustrations and hopes. HIV Effect Diagram Epidemiological History of AIDS: Stage 1: 1981-1986 Untreatable Stage First AIDS Case Discovered in 1981 One morning in 1981, my wife came home from her shift at the UCLA Medical Center to tell me that she had just taken on a depressing new case there. The patient's name was Queenie, he had dyed yellow hair, and he was a male prostitute who was only eighteen years old. When he first arrived in the emergency room, he was running a high fever and coughing constantly, seemingly suffering from common pneumonia. He was supposed to be treated with antibiotics, but the medical team found a bacteria called Pneumocystis carinii in his lungs. This bacterium is known for its ability to cause fungal pneumonia and is usually found in severely malnourished children, as well as adults who have received organ transplants or chemotherapy. The hospital called in several specialists to analyze the symptoms of this infection. queenie's platelet levels were very low, which made him prone to bleeding, and I was called in to examine him. He was lying on his side, breathing hard, and the sheets were soaked with his sweat. He had a very bad herpes infection, so much so that the surgeon had to remove the area of his thigh that had been eroded by an abscess. I also could not explain why his platelet levels were low. His lungs began to fail and he was dependent on a respirator. Shortly afterward, he died of respiratory failure. The rare pneumonia he developed has been seen on both the east and west coasts. Michael Gottlieb, an immunologist at UCLA, analyzed blood samples from some of these patients and made a major discovery-these patients had lost almost all of their helper T cells, which protect the body from infection and cancer.In June 1981 The Centers for Disease Control published Gottlieb's findings in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. In July of the same year, Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien of New York University reported that 26 gay men in New York and California had been diagnosed with Kaposi's sarcoma - a cancer of the lymphatic vessels and blood vessels. The phenomenon is also curious because usually only older men of Eastern European Jewish race or Mediterranean descent group ethnicity are infected with Kaposi's sarcoma. I was responsible for the care of these Kaposi's sarcoma patients. At that time I was only the most junior member of the staff and had no expertise in oncology, but no senior faculty member would take this kind of job. My first case was a closeted gay man, nicknamed Bud, who lived in West Los Angeles and was a middle-aged firefighter. Not long after he was admitted to the hospital, hyperplastic tissue like ripe cherries began to grow on his legs, then spread to his torso, face, and even his mouth. Despite intense chemotherapy, as is the standard of care for advanced Kaposi's sarcoma, the tumors continued to grow, eating away at his body and appearance and claiming his life within a year. By 1982, cancer patients with various malignant lymphomas began to appear in the hospital. Chemotherapy failed to help them as well. Patients died from a variety of diseases due to the destruction of their immune systems. All of my patients suffered from the same disorder, which the Centers for Disease Control named "Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome," or AIDS, that same year. At the time, scientists did not know what caused the disease. The following year, two research teams - led by Luc Montagnier and Francoise Barré-Sinoussi at the Institut Pasteur in Paris and Robert Gallo at the National Cancer Institute in Maryland - published a paper in the journal Science. -have published several articles in the journal Science describing a new retrovirus found in the lymph nodes and blood cells of AIDS patients. The retrovirus reproduces in a malignant way: it permanently inserts DNA from its own genes into the nucleus of a host cell, hijacking the cell's machinery for its own perpetuation. When retroviruses mutate (and they usually do), it is very difficult for the human body or a vaccine to target and destroy them, so they multiply. It was once widely believed that retroviral diseases were incurable. In May 1986, after much debate over exactly who should be credited with the discovery, the International Scientific Committee finally named the virus H.I.V., Human Immunodeficiency Virus. By the end of that year, of the nearly 29,000 Americans diagnosed with AIDS, about 25,000 had died. (The French team was eventually awarded the Nobel Prize in 2008 for the virus, which was finally named H.I.V. by the International Scientific Committee in 1986 and is a treatable disease.) Since then, AIDS has become a treatable disease, one of the great victories of modern medicine in the fight against disease. Phase II: 1987-1996 The development of antiretroviral drugs In 1987, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved AZT, an abortive cancer drug for use by AIDS patients. Initially, the drug was very expensive and prescribed in high doses, and later proved to be somewhat toxic, thus causing opposition from the gay community. However, AZT was able to sneak into the DNA of the virus as it formed, and its dosage was later reduced. Scientists have now developed more than three dozen antiretroviral drugs that prevent HIV from multiplying in helper T cells.

Phase III: 1997-2006 The Quest for a Cure for AIDS In the 1990s, a combination of drug therapies - a "cocktail" of therapies - emerged, drawing on the approach taken by oncologists to the treatment of cancer. -- It drew on the approach that oncologists have taken to treating cancer. Like HIV particles, cancer cells are able to mutate quickly and escape the tracking of a single targeted drug. Prominent researchers such as David Ho from the Aaron Diamond Center for AIDS Research in New York have put a treatment regimen - HAART, also known as highly active antiretroviral therapy - into clinical trials. I call this "cocktail". I gave this "cocktail" to one of my patients, David Sanford, and within a month of starting the regimen his fever was gone, his infection had disappeared, and he was beginning to regain his energy and weight. His bloodstream was nearly cleared of HIV, and he showed no signs of relapse. Subsequently, Sanford wrote in a Pulitzer Prize-winning article, "Perhaps my chances of being hit by a truck are even higher than my chances of dying of AIDS." The survival of the majority of AIDS patients in the United States now fulfills that statement. In the past five years, none of the many AIDS patients in my care has died from the disease. But the road remains bumpy. There are now 35 million people living with AIDS worldwide. In sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest number of new AIDS cases, 63 percent of those eligible for medication do not receive it; and even those who do receive it do not receive a full course of treatment. In the U.S., the average year of HAART treatment costs thousands of dollars per patient, and the long-term side effects can be debilitating. Now, researchers are increasingly beginning to explore a cure for HIV. We know about HIV to the extent that we know about some cancers: HIV's genes have been sequenced and the way it invades host cells deciphered and its proteins mapped in three dimensions, and in 1997 a major discovery was made: the virus is able to lurk in long-lived cells, where current medicines can't affect it. If we can remove the viral reservoirs safely and economically, we will finally defeat AIDS. On January 1, 1983, San Francisco General Hospital opened Ward 86, the first AIDS clinic in the U.S. Recently, I visited Steven Deeks there, an expert in AIDS-induced chronic immune activation and inflammation, and a professor at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine. He is also a professor at the UCSF School of Medicine, where he conducts the SCOPE study: a study of 2,000 HIV-positive men and women to measure the long-term effects of the virus on the body. Each year, these blood samples are sent to laboratories around the world, and Deeks is tasked with categorizing the damage that HIV does to human tissues and testing new drugs that might be effective. The clinic occupies the entire sixth floor of an art deco building on the north side of campus. I find Deeks in his office, wearing a facecloth top and New Balance running shoes. He explains to me his concerns about cocktail therapy. "Antiretroviral drugs are designed to stop HIV from replicating, and they do work," he says. But many patients cannot be fully restored to health with the help of drugs. The immune system improves enough to stop AIDS, but because the virus is so persistent, the immune system must respond at a consistently low level. This leads to long-term chronic inflammation, which causes tissue damage. San Francisco General Hospital, the first AIDS clinic ward 86 on the sixth floor of this building Inflammation can also be exacerbated by side effects from the drugs. Early treatment triggers anemia, nerve damage and impaired fat metabolism - fat disappears from the limbs and face and is deposited in the abdomen. Lipodystrophy remains a major problem in the treatment of AIDS, and Deeks found that many of his patients in the SCOPE study had high cholesterol and triglycerides, which can lead to tissue damage and, as a serious consequence, heart disease that appears to be triggered by inflammation of the artery walls. Deeks also found that his patients developed lung, liver and skin cancers. In the early recurring symptoms of the epidemic, he found that middle-aged patients develop other diseases as they age: kidney and bone disease, and possibly neurocognitive deficits. In Deeks' view, a better definition of AIDS might be "acquired inflammatory disease syndrome". He introduces me to one of his patients, whom I'll call "Gordon". A tall, kindly man with rimless glasses rose to shake my hand, and I saw his trademark bulging belly. He has had AIDS for almost forty years and says he feels lucky to be alive: "My partner of ten years had the same AIDS, we ate the same food, went to the same doctors, received the same AIDS treatment early on, and he died in June 1990, about twenty-five years ago." He told me, "I don't worry about HIV itself anymore. I'm more worried about my internal organs and early aging." In 1999, at the age of fifty, he learned that fatty deposits can drastically curtail blood flow in a major artery, the main nutrient-supplying artery to the left ventricle of the heart. He began to feel pain when he walked due to the reduced blood supply to the bone tissue - this because this virus is stubborn and the immune system must respond at a consistently low level. This can bring on long-term chronic inflammation, leading to damage to the tissues.He had his first hip replacement in 2002 and a second surgery in 2010. His muscles have atrophied and he can't sit comfortably, so he sometimes has to wear special foam padded underwear. Every other year, he receives injections of poly-L-lactic acid into his face to replace the lost connective tissue, and Gordon's prolonged life, along with the numerous medications he takes to keep him alive, is typical of the experience of countless people living with AIDS. The state-of-the-art treatment he received cost $100,000 a year. Although these costs are covered by his insurance and the state of California, he refers to them as a "ransom: it's money or life." But for Deeks, the question is, "Can the world find enough resources to build a system that delivers antiretroviral drugs to about 35 million people a day, many in poor neighborhoods?" He was skeptical, which is why he focused his efforts on finding a cure for AIDS. In 1997, while there was deep rejoicing over HAART therapy, serious thought was being given for the first time to a complete cure. "The idea was that in order to cure AIDS, we needed to know where it was coming from and why it was so persistent," he says. HIV proved to be smarter. It lies dormant in the host's DNA strands, where a cocktail of therapies can't work on it, and then the virus will revive and destroy the body's immune system, and sooner or later all the infected cells will die out on their own. Would the exact combination of the right drugs destroy the virus once and for all? In the same year, David Ho published an article in Nature in which he numerically predicted that AIDS patients on HAART could beat the detectable virus within 28 to 37 months. This issue of Nature also features an article from Robert Siliciano, now a researcher at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Siliciano discovered HIV in a type of helper T cell that provides memory for our immune system, and which normally lives for decades. Memory T cells are extremely important: they recognize antigens in an infection and respond quickly. But HIV has proven to be smarter. It lies dormant in the host's DNA strands, where cocktail therapies fail to work, and the virus then revives and destroys the body's immune system. Prof. Steven Deeks (left) and Prof. Robert Siliciano (right) Husband and wife Siliciano's fundamental discovery about HIV Siliciano, 62, is highly respected in the field of AIDS research. He met his wife and collaborator Janet, 57, with curly red hair, in the 1970s and she joined Bob's lab after his paper was published in Nature. She says the idea came from Bob, but Bob tells me that Janet developed it over the next seven years, tracking the levels of dormant viruses in patients who continued to be treated with HAART. Her data proved his contention that the virus could survive almost indefinitely. "We calculated that it would take up to seventy years of continuous HAART therapy to kill all the memory T cells." She said. Siliciano recounted to me how he first discovered the latent virus on the memory T-cells of an AIDS patient on HAART therapy. At the time, it was thought that this patient had been cured. "We biopsied him everywhere we could think of, and nobody found any HIV," Siliciano said. The researchers took twenty tubes of the patient's blood, isolated the T-cells, put them in multiple test tubes, and then mixed those samples with HIV-uninfected human cells. If the healthy T-cells were infected, then HIV would begin to multiply and be released. Siliciano remembers sitting at a table talking to a visitor when a graduate student burst in, "Those tubes are turning blue!" Siliciano remembers that he was sitting at a table talking to a visitor when a graduate student came in and said, "Those tubes turned blue!" He recalls, "It was a very peculiar moment because it confirmed the hypothesis, which was exciting, but it was also a catastrophe. Everyone came to the same conclusion: despite antiretroviral treatment, these cells were stubbornly surviving." Much of the new AIDS research builds on the Siliciano couple's foundational discovery that HIV hides in host cells. By using a number of potent chemicals, they were able to extract HIV from their hiding place in memory T cells as a way of assessing how far the virus had spread through the body and began to map markers on other body parts where they might be distributed. These two examples confirm that researchers are on the right track in attacking latent infections, providing a "proof of concept" that latent HIV in the human body may be removable. The method of removal may be risky and toxic, but it is only a proof of concept. Although the researchers were dismayed to realize that the drug therapy itself was not a cure for HIV, their recent discovery of three unusual cases is encouraging and keeps them on the search for a cure. Phase 4: 2007-2011 Case experience and validation phase of the quest for a cure The first case is that of Timothy Ray Brown The first and only person to be cured of AIDS, Brown is known as the "Patient of Berlin" In 2006, more than a decade after he found out he had AIDS, he was diagnosed with a homozygous AIDS patient who had been diagnosed with the same disease. In 2006, more than a decade after he found out he had AIDS, he was diagnosed with a disease unrelated to AIDS - acute myelogenous leukemia, a cancer of the bone marrow. After initial treatment, the leukemia returned, and Brown needed a bone marrow transplant. His hematologist, Dr. Gero Huetter, made an imaginative suggestion that they use the bone marrow of a donor who had a genetic mutation that prevented the production of the CCR5 protein, which is the pathway by which HIV enters helper T-cells. on February 7, 2007, Brown received a bone marrow transplant. A year later, he had a second transplant, and by 2009, Brown's biopsy revealed no trace of the virus, and his T-cell counts had returned to normal. Brown's eventual cure was a miracle, but one that would be difficult to replicate, as his doctors destroyed his own blood cells twice with radiation and chemotherapy, and rebuilt his immune system twice with stem cell transplants. This approach is extremely dangerous and expensive. The researchers wondered if they could create a scaled-down version of the treatment program. Second Case: The Boston Patient Case - Two HIV patients treated with HAART received bone marrow transplants because they had lymphoma In 2013, doctors at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston reported the results of a study in which, unlike Brown, their bone marrow donors did not develop the CCR5 mutation and received less intense and less dense chemotherapy than the latter. After receiving their transplants, they took a break from HAART treatment for several years, and although HIV was undetectable for several months, the virus eventually reappeared in their bodies. The third case: "Mississippi Baby" In July 2013, the results of the third case were also available: in 2010, a mother with AIDS who was not taking antiretroviral drugs gave birth to a baby girl, known as "Mississippi Baby," who had HIV in her blood. The baby had HIV in her blood. Thirty hours after birth, the newborn began receiving antiretroviral treatment. Within a few weeks, the number of viruses in the baby's body was reduced to below detectable levels. At eighteen months of age, the baby failed to comply with medical advice and discontinued treatment. For up to two years, no trace of the virus was found in the baby girl's blood, and researchers hypothesized that that early HAART treatment may have prevented the virus from forming a dormant storage pool. However, 27 months after the baby girl's medication was discontinued, she was detected with the virus in her system. She was not cured, even though the researchers felt that early intervention could temporarily banish HIV. In August, Janet and Robert Siliciano published articles in Science about the Brigham male patient and the Mississippi baby, mentioning that both cases confirmed that researchers were on the right track in attacking latent infections. The Berlin patient is a more high-profile case. Karl Salzwedel, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told me that before the Timothy Brown case came along, "it was not clear how we were going to be able to get rid of the last vestiges of the virus. "Brown's case provided a " proof of concept that latent HIV in the human body may be removable. Removal methods may be risky and toxic, but this is only a proof of concept."

Phase V: 2011 - 2030 Countdown to a Cure, End AIDS Phase (a) 2011-2013 Launch of a World Collaboration with Different Strategies and Multiple Directions Exploring the AIDS Cure Phase The newest mainstay of the U.S. commitment to finding a cure for AIDS is the Martin Delaney Collaboratory, which was Funded by the (U.S.) National Institutes of Health (N.I.H.) and launched in 2011, it unites a number of clinical laboratories, research laboratories and pharmaceutical companies. With support from all parties and open communication, federal funding for the lab is set at $70 million for the first five years. Salzwedel told me N.I.H. is funding three applications. "Each is taking a different and complementary approach to trying to develop a strategy that will eradicate AIDS," he said: boosting the patient's immune system, manipulating the CCR5 gene, and disrupting the viral reservoir itself. They represent different responses to Siliciano's theory and the experience gained from the Timothy Brown case. Strategy One: Mike McCune, head of the Division of Experimental Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, approaches the study from the perspective of eradicating HIV with the help of the body's own immune system. He drew insights from early observations of the virus' development: babies born to mothers with AIDS had only a five to ten percent chance of contracting the disease in the womb at the time, even though they were exposed to the virus throughout their pregnancies. More recently, McCune and his colleagues observed that the developing fetal immune system does not respond to maternal cells, which can easily cross the placenta and eventually reach fetal tissue. Instead, the fetus produces specialized T-cells that inhibit an inflammatory response to the mother, which may also protect the baby by preventing an inflammatory response to HIV, which in turn prevents the rapid spread of the virus in utero. Babies born to mothers with HIV had only a five to ten percent chance of contracting the disease in the womb at the time, even though they were exposed to the virus throughout their pregnancy. In July 2013, a mother with HIV who was not taking antiretroviral drugs gave birth to a baby girl known as "Mississippi Baby. McCune has been working with Steven Deeks and SCOPE research for years. When I interviewed him in San Francisco, he said, "There is a yin and a yang in the immune system. We're trying to recreate the core of that exquisite balance found in the womb." McCune, who is currently working on interventional studies as a way to prevent AIDS-induced inflammation in adults, hopes to mimic the balance found in the womb to some degree. He is also working on methods that will allow the immune system to better recognize and destroy the virus when HIV is exposed. These studies are currently being conducted in nonhuman primates and may progress to human trials in a year or two. Strategy Two: In Seattle, a team headed by Hans-Peter Kiem and Keith Jerome is taking a more futuristic approach to research. They are using an enzyme called "zinc finger nuclease" to genetically alter blood and bone marrow stem cells by disabling the CCR5 gene (CCR5 is required to infect T cells). The researchers will modify the stem cells in vitro so that when the cells are returned to the body, some of the T cells in the blood will become resistant to HIV. They hope that, over time, these cells will begin to multiply and the patient will slowly build up an immune system that is able to fight off HIV. A small reservoir of HIV may still remain in these patients, but their bodies will be equipped to control the infection. Strategy 3: David Margolis leads the largest collaborative lab, which is located at the University of North Carolina and has more than 20 members.Margolis is an infectious disease specialist who is directly targeting the HIV storage pool. His idea, also known as "activation-destruction," aims to activate dormant viruses, unmask the virus-carrying cells, and then destroy them. in 2012, he published the results of a clinical trial using the drug vorinostat, initially developed for T-cell blood cancers, in a shock therapy. This past October, when a team from a collaborative lab When the Collaboratory team gathered at N.I.H. this past October, along with hundreds of other researchers, scholars and interested laypeople, "activation-destruction" therapies were widely discussed. During the discussion, Margolis and his team explored new ways to activate viruses from their dormant state. Therapeutic vaccine strategies: The elimination phase is more challenging because these activated cells carry small amounts of HIV antigens, and the toxic markers released by the disease-causing particles are recognized by the immune system before they can be attacked. One of the ways in which the elimination strategy is achieved is through an uncommon type of AIDS patient who may "live peacefully" with the virus for decades. Some of these so-called "elite controllers" or killer T-cells are cytotoxic and can attack virus-producing cells. The goal is to give every AIDS patient a "therapeutic vaccine" with elite controllers that will allow the patient to spontaneously produce killer T-cells. Other strategies: Researchers are also trying to turn off a molecule called "PD-1," which the body relies on to suppress the immune system. PD-1 has been blunted and effective in clinical studies of melanoma and lung cancer, and one patient appears to have been cured of hepatitis C simply by injecting a PD-1 blocker from Bristol-Myers Squibb. There are groups outside the collaborating labs that are also testing various AIDS cures and sharing their results. In addition to the Seattle team, Carl June, director of translational research at the University of Pennsylvania's Abramson Cancer Center, and his colleagues used genetic engineering to turn off the CCR5 channel. They published a report on their recent clinical trial in the New England Journal of Medicine in March, noting that the modified T cells were able to survive for years in AIDS patients. Calimmune, a California-based company dedicated to curing AIDS, is doing similar work to remove CCR5 (one of the company's founders is David Baltimore, who won a Nobel Prize for his discovery of reverse transcriptase, an enzyme important in reverse transcription replication). Teams in Denmark and Spain have also made important advances in their respective fields of research. In 2012, French researchers analyzed the Visconti study, which converted an early intervention treatment received by Mississippi babies into a formal trial. A group of fourteen AIDS patients who were infected received the treatment for several weeks afterward, and then HAART treatment was interrupted. Several years later, none of them had detectable virus in their bodies. (ii) 2014- ? Long-Term Remission and Functional Cure Phase In July 2014, at the 20th World AIDS Conference in Melbourne, Australia, Sharon Lewin, an infectious disease expert from Monash University, said, "At this point, we're probably still looking to try to do our best to achieve long-term remission." Most experts agree that remission is achievable, and that in some ways we will be able to wean patients off lifelong treatment. Even the most cautious AIDS researchers believe that a cure will eventually be achieved after long-term remission, and Robert Siliciano told me, "The primary goal is to shrink the pool of HIV. This is not just for the individual, but will have public health implications." Regardless of how long a patient has been off HAART treatment, doctors will be able to shift resources to those who still need treatment. David Margolis believes his "activation-elimination" strategy will eventually work, but it may take 10 to 20 years, and the Silicianos agree that more research is still needed. "The more we learn, the more questions we have to answer," Janet told me. Janet told me. (iii)? --2030 Long-Term Mitigation to End of Epidemic, End of AIDS Phase Summary and Outlook: Questions that have long been answered continue to amaze AIDS scientists to no end. In the early years of the HIV epidemic at UCLA, I never imagined that future patients would live into their eighties. A deadly virus had been tamed into a chronic condition. The next step was to find a cure. Scientists are naturally curious, and AIDS researchers have learned humility over the years. Scientific advances have always been surrounded by uncertainty, intertwined with frustration and hope.

In the subconscious of many people, having AIDS is equivalent to a death sentence. But recently, a British AIDS patient, after receiving a stem cell transplant, the body of the AIDS virus has disappeared! The news shocked the medical profession. Can AIDS, which has plagued mankind for many years, really be cured?

AIDS didn't start with people, it was only transmitted between animals, first found in African primates. Until that day, when the moon was dark and the wind was high, and some guy and a chimpanzee were...indescribable...

In parts of Africa, it has been customary to eat chimpanzees. Therefore, scientists speculate that human beings were infected with the virus when they hunted or ate chimpanzees, and that the virus was later spread around the world through blood, mother and child, and sex.

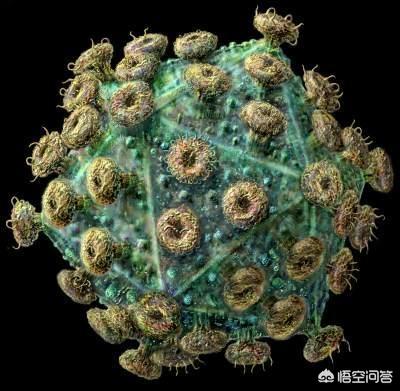

These HIV viruses come on strong, they attack the immune cells and dismantle the body's immune system defenses step by step, leaving you with a cough, fever, enlarged liver and spleen, and complications of malignant tumors ......

For more than 30 years, more than 35 million people have died of AIDS, and there has been no cure. Until he came along ~ German boy Timothy Ray Brown, the first person to be cured of AIDS.

In 1995, Brown was diagnosed with AIDS and relied on daily antiretroviral drugs to contain the spread of the virus. It was hard to get the disease under control, but in 2006, he was diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia. Without a bone marrow transplant, he might not last more than a month.

At that time, Brown's primary care physician, Jello Huttle, decided to find another way. Since he was going to transplant, why not just do something else~ Research has found that a very small number of white Europeans are naturally resistant to AIDS, containing mutant CCR5 purists in their bodies that prevent the AIDS virus from entering the immune system. Even when exposed to the virus, they don't get infected!

So what if the bone marrow from these people was transplanted to Brown, maybe it could cure the two deadly diseases in Brown in one fell swoop. After 2 bone marrow transplants, a miracle really happened! Brown's leukemia and AIDS were all cured and never returned.

BUT initially the doctors who heard the news were calm and thought it was totally his luck ~ stepping on shit ~ until the recent news that the British AIDS patient was cured, which made countless doctors' eyes light up.

Because their cases are so similar, the British patient, who also suffered from two deadly diseases, advanced Hodgkin's lymphoma and AIDS, was able to get his disease under control after a transplant of bone marrow containing a mutant CCR5 pureblood, and has not relapsed since! This shows that Brown's healing is not a coincidence and can be replicated.

Did we beat AIDS? Not really. First of all, the number of eligible bone marrow donors is extremely rare, only two in a billion. It's hard to find an average bone marrow donor, let alone one who carries the mutant CCR5 pureblood, in a sea of people. Secondly, any transplantation is subject to rejection, and it takes time to verify whether the immune system can recover, to what extent, and whether there will be a relapse. So yes, it is too early to talk about a cure.

At present, the most effective means of dealing with AIDS is still prevention, prevention, prevention! There is a knife in the head of the word "sex", especially good-looking boys, must learn to protect themselves ah~!

When will AIDS be cured? This question touches the nerve of every one of us!

What is AIDS?

AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Dyndrome) is an extremely dangerous and virulent infectious disease caused by infection with the AIDS virus (HIV), a virus that attacks the body's immune system, causing the body's immune system defects. It takes CD4T lymphocytes, the most important cells in the human immune system, as its main target and destroys them in large numbers, causing the body to lose its immune function. Therefore, after being infected with AIDS, the human body is easy to be infected with various diseases, and malignant tumors can occur, with a high rate of death.The incubation period of HIV in the human body is 2-10 years on average, with the shortest period being half a year, and the longest period being as long as 25 years, and before suffering from AIDS, the person can live and work for many years without any symptoms.

Since 1981, when AIDS was first reported in the United States, it has rapidly swept across the globe in just a few decades, and to date there are about 35 million infected and sick people worldwide. In 1994, Chinese-American scientist He Dayi researched "cocktail" therapy to treat AIDS, which is a combination of protease inhibitors, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and can treat AIDS more effectively. Therefore, AIDS has become a preventable, controllable, but incurable (or functionally curable) disease.

When will AIDS be completely cured?

There is no answer to this question, but scientists are now doing all sorts of research, and there has been a great deal of progress in research, with many antiviral drugs being introduced. The "Berlin Patient" Brown is currently the only case in the world to have been "cured" of AIDS, so there is a lot of research surrounding him, and there have been a lot of breakthroughs, and we believe that AIDS can be completely cured in the near future.

Functional cure for AIDS

Let's take an example, the famous American NBA star "Magic" Johnson was diagnosed with AIDS in 1991, but now more than 20 years later, he is still living a healthy life, and also became the president of the Lakers team! One of the patients I manage was diagnosed in 2004, started taking medication in 2015, and is still in good health. So as soon as you find out that you are infected with HIV, then it is important to stay in a good frame of mind and take your antiretroviral medication on time and in the right dosage. Treatment is proven to be effective when the CD4T is within the normal range, as well as when the HIV viral load is below the lower limit of detection.

Many people think that the drugs for the treatment of AIDS have a lot of side effects, this can be clearly said, chemical drugs have side effects, the first three months of the first medication will indeed be a little difficult, but after three months after a few days of tolerance, there is basically no effect. Now the conventional treatment drugs are lamivudine (3TC), tenofovir (TDF), efavirenz (EVF) and other six, the first two are also commonly used in the treatment of hepatitis B, the safety is very high.

I am an infectious disease doctor, long-term treatment of AIDS patients, which is often asked by patients with AIDS, from the discovery of AIDS in 1986 to now more than 20 years, compared with other diseases, this is a relatively new disease, now there are a large number of scientists, medical workers in the study of AIDS, but also invented a cocktail of therapies for the treatment of AIDS, in terms of medication, there have been a variety of anti-AIDS drugs, the In terms of drugs, there have been many kinds of anti-AIDS drugs, which are more effective and have fewer side effects than those of the previous generation, and we believe that AIDS will be conquered in the near future.

Follow Dr. Lee and be with me on the road to health!

My father is a medical researcher, and he once said that in the next century, that is, in the 21st century, many difficult medical problems can be solved, including mental illness, cancer, and I believe that AIDS can be solved as well. Of course, sometimes I still think that I can't solve the problems for the time being, but I can only hope for the help of aliens. I really hope that there will be aliens to help those people who are suffering!

This is a problem that is not a problem. There are two kinds of people who are really concerned about it: those who are AIDS patients, who, of course, want it as soon as possible. The other group of people, the businessmen, especially the Western pharmaceutical moguls, are very reluctant to eradicate AIDS. So it's a very difficult east...east...when to eradicate it.

Eradicating AIDS will have to wait for new scientific research. But blocking and combating it is still very effective!

AIDS blocking drugs

HIV blocking pills, which are used to prevent the spread of the HIV virus after having high risk behavior. The correct time to take the blocking medication is within 72 hours! Within this period, the virus has not spread from the initial infected cells to other cells. The medication will not kill the virus, but it is effective in controlling the spread of the virus. Over time, the virus-infected cells die and the virus fails to spread to new cells, which are then cleared by the body. The failure rate of HIV blockade is probably around 5/1000.

AIDS is not scary.

Upon diagnosis of HIV infection, clinical and laboratory evaluation should be carried out in a timely manner and antiretroviral treatment should be initiated at a hospital designated for AIDS treatment. In the latest edition of the National Free HIV Antiretroviral Drug Treatment Manual, there are eight types of free drugs. At present, about 90% of AIDS patients' medication is based on free national drugs.

About 30 antiretroviral drugs are currently available for HIV antiretroviral therapy. Antiretroviral therapy is a combination of at least 3 different medications used to inhibit HIV replication based on the principle of drug combinations, commonly known as "cocktail therapy". Antiretroviral therapy is the most effective treatment available! Although it does not remove the HIV virus from the body, it is effective in reducing the amount of the virus, reducing the damage it does to immune function, and thus prolonging life.

Today, although there is no cure for AIDS, the disease no longer means "death sentence"! CD4 cells are an important immune cell in the body's immune system, and the normal adult CD4 cell count is 500-1600 cells per cubic millimeter. Studies have shown that within one year of starting treatment, AIDS patients can reach a CD4 cell count of 350 cells per cubic millimeter, and at the same time have an undetectable viral load and are predicted to have a normal life expectancy.

With advanced antiretroviral therapy, AIDS has been transformed into a chronic disease. As you can see, AIDS is not that scary! With early detection, early treatment and long-term treatment, people living with AIDS can still live a long and healthy life.

It is said that cancer is a terminal illness, and cancer is a terminal illness. In fact, the Chinese medicine of "against the dang soup" under the blood storage is a case of curing cancer, folk doctors is to use insects plus herbs to cure cancer, just do not let the license plate. AIDS is the same reason, so you say can be cured, there will be no believers, this is a great victory of science ah!

There may be a cure one day, that would require a highly advanced medicine and a highly advanced economy. The best way is to be clean. If you are infected, live well and love life.

How is it that the great and scientific Western medicine is curing everything, and how is it that today it is asking when mankind will cure AIDS?

I'll tell you what the subject matter is, treating diseases is a western medicine specialty, there is no disease that western medicine can't treat, but there is no disease that can be cured either, at most a short period of time anti-inflammatory, that's all.

The questioner probably wants to ask when advanced medicine will be able to cure AIDS, right? Western medicine can cure any disease, but I can tell you responsibly that Western medicine can't cure any disease. Therefore, diseases still rely on prevention. Follow nature, strengthen self-protection, do not expect modern medicine can cure your disease, the money to leave the disease away, this is the "science" of Western medicine.

This question and answer are from the site users, does not represent the position of the site, such as infringement, please contact the administrator to delete.